This began when Dr. deLucia was completing his Ph.D. and simultaneously starting consulting and conducting research in the late 60s until the 1980s. During this time, he was immersed in the international development space dominated by the major development assistance and finance organisations, such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and others. During this period, his work included:

- Policy, public finance and technology in the rapidly evolving environmental financing and regulatory space resulting from the creation of the US Environmental Protection Agency and its initial enabling legislation;

- Various regional economic development efforts supported by other public finance initiatives and financial intermediation mechanisms;

- Micro- and macro-economic international development work addressing policy and techno-economic investment work perhaps best illustrated by his consulting activities during the first Sahel crisis of the 1970s and his role in leading one of the teams that prepared the first Energy Sector Plan for the then-new country of Bangladesh;

- Various business and private investment experiences, including becoming a founding principal in two consulting groups through which almost all of the efforts prior to S3IDF were undertaken and multiple private projects investing and implementation efforts (both social and commercial) as well as other less active roles in investing, all of which enriched his understanding of capital markets and markets in general; and

- Several adjunct/part-time teaching, professional research, writing and professional association services roles, including, most notably, a collaboration with the late Professor Ramesh Bhatia, who would become a life-long collaborator, friend, and co-founder of S3IDF.

The Need for New Development Paradigms

First Phase

By the late 1980s, as a result of Dr. deLucia’s work in the international development space, specifically with the activities of major (and some minor) bilateral and multilateral development assistance and finance entities (e.g., IBRD, ADB, USAID, DFID, FAO, etc.), Dr. deLucia had a new and much more extensive network.

This network consisted of consultants and advisors who, like him, had worked extensively with the aforementioned development assistance and finance entities. This network also included a number of practitioners and officials who worked for the recipient governments and various civil society and private sector organisations.

A subset of this network were individuals who he came to know quite well (or knew previously, some from his “Cambridge-centric” network) and respected and with whom he began “on the side” conversations while on assignment in different countries for the entities mentioned above. These dialogues were about the shortcomings of the common/conventional paradigms of economic development. Despite good intentions, economic development approaches typically failed to serve poor and marginalised communities effectively and/or sustainably reducing the odds that these communities could escape poverty.

The projects and programmes under the dominant paradigms were rarely structured to develop sustainable local market systems of small players and projects. They often ignored the then rapidly evolving technological and materials advancements that were making small-scale infrastructure investments viable. This was problematic since access to affordable and reliable modern infrastructure services, such as electricity, provides a foundation from which to improve both lives and livelihoods. The conventional paradigms also tended to overlook the capabilities of local private players (often in the informal sector but with entrepreneurial upgradeable skillsets) and critical development synergies such as between infrastructure financing and local capital market development, not to mention institutional and cost-effective synergies from bundling of services (e.g., water, electricity, and telecommunications). Instead, the dominant paradigms espoused “trickle-down” economics, focusing on economies of scale of large infrastructure construction, emphasising regimented institutional arrangements (customer, supplier and policymaker relationships), and often prioritising private international players and capital markets with the effect of downplaying if not totally ignoring local capacities.

These first phase dialogues enriched Dr. deLucia’s thinking immensely as it evolved and focused especially on the shortcomings in areas of physical infrastructure access (or lack thereof) and poverty alleviation linkages. Particularly important were dialogues during and around his participation in an advisory group supporting IFAD’s State of the World Rural Poverty study, during which he authored his seminal work, The Energy Dimensions of Poverty. It warrants underscoring that IFAD work approach resulting from its unique mission (and funding and governance structure) did not generally suffer from the shortcomings highlighted above.

Second Phase

As Dr. delucia’s thinking continued to evolve, a second phase of dialogues began with a group drawn from the prior networks who had expressed unwavering commitment to give regular and often considerable “pro-bono” time to conceive and implement a new approach to address the shortcomings of conventional paradigms.

This small group, who in the end would become co-founders of S3IDF, represented a wide-ranging set of experiences appropriate to the challenges of addressing the nexus of issues pertinent to poverty alleviation in the developing world. Moreover, their skills were complementary in various ways, especially their extensive global expertise; collectively, they had worked in more than 70 countries and had all focused on poverty alleviation challenges in numerous urban and rural settings. All knew one another to varying degrees, but Dr. deLucia knew them all well and was a lynchpin of their development dialogues.

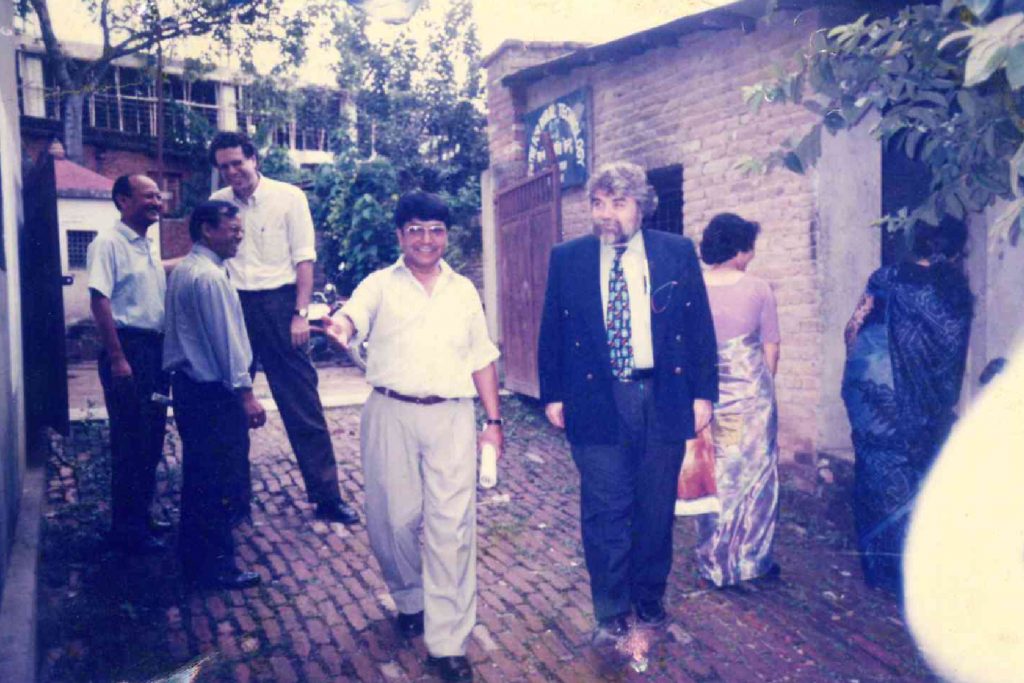

During this second phase, the dialogues among this group occurred organically when members happened to on assignment in the same developing countries and could coordinate conversations (subject to their “regular” professional responsibilities). However, this phase of the dialogues benefited significantly from Dr. deLucia, Professor Bhatia and Mr. Barnett (the overall organiser and responsible initiative lead). Mr. Barnett was part of a team of international experts that designed and directed a multi-country International Development Research Centre (IDRC) research initiative. In this initiative, country-specific teams researched projects and policies and exchanged ideas with each other and with international experts. The IDRC initiative required much travel and many short meetings throughout Asia, Latin America, Africa, and North America. The travel and meetings allowed many for regular “on the side” discussions of matters pertaining to S3IDF’s conceptualisation. The group’s discussions also benefited from interactions with the local teams whose members were also very experienced in the energy access-infrastructure and poverty alleviation nexus given their own work experiences.

This second phase of dialogue led Dr. deLucia and his colleagues to formulate the basis of an approach to address the conventional paradigm shortcomings by giving particular attention to infrastructure services that, when paired with bundled support, could make it possible for communities to escape the “ecosystem of poverty.” Discussions often built on outlines or concept notes, generally draughted by Dr. deLucia and revised based on feedback.

By this time, the conventional paradigms of the major multilateral and bilateral development entities were beginning to evolve. Projects and programmes started to have increased private participation, public-private collaborations, and innovative financial engineering and risk management. While a positive direction, these changes were almost exclusively designed for and implemented in larger projects and programmes, meaning that many of the benefits continued to bypass the poor and underserved communities. There were, however, positive changes emerging, most notably technological innovations that made small-scale investments, such as improved solar cells, batteries, and micro-hydro systems, much more competitive and creating other development synergies. These discussions, and the critical concepts that emerged, provided the foundation for S3IDF.

S3IDF Takes Shape

The S3IDF founders, leveraging their knowledge and experience, seized the opportunity to build on the evolving development paradigms and extend the benefits into poor and underserved communities. The S3IDF concept explicitly embedded principles and approaches to bring engineering, institutional, and financial engineering approaches that had evolved for large projects and brought them to bear on small projects. Projects and programmes would be implemented explicitly with pro-poor, pro-environment criteria and business-like thinking. The approach became known as The Social Merchant Bank Approach (SMBA)®.

The SMBA was designed to address the problems the poor face by simultaneously overcoming their lack of access to financing, technology access and knowledge, and/or business experience by using innovative co-financing mechanisms and on-the-ground support. By bundling and tailoring support in these areas to local conditions and market demands, S3IDF set out to enable the poor to gain access to basic services, employment, and asset-creation opportunities. These benefits also would help to improve standards of living and stimulate economic development.

The founders, through S3IDF, set out to pursue two parallel mission objectives:

- Positively impact the poor and the environment by employing the SMBA® in India; and,

- Achieve broader and greater impact within poor communities around the globe by challenging current development practises and mindsets as well as enabling other development entities to effectively apply the SMBA®.

Read more about key moments in S3IDF’s history here.

The Founders

Mr. J. Andrew Barnett

Professor Ramesh Bhatia

Dr. Russell J. deLucia

Mr. Michael C. Lesser